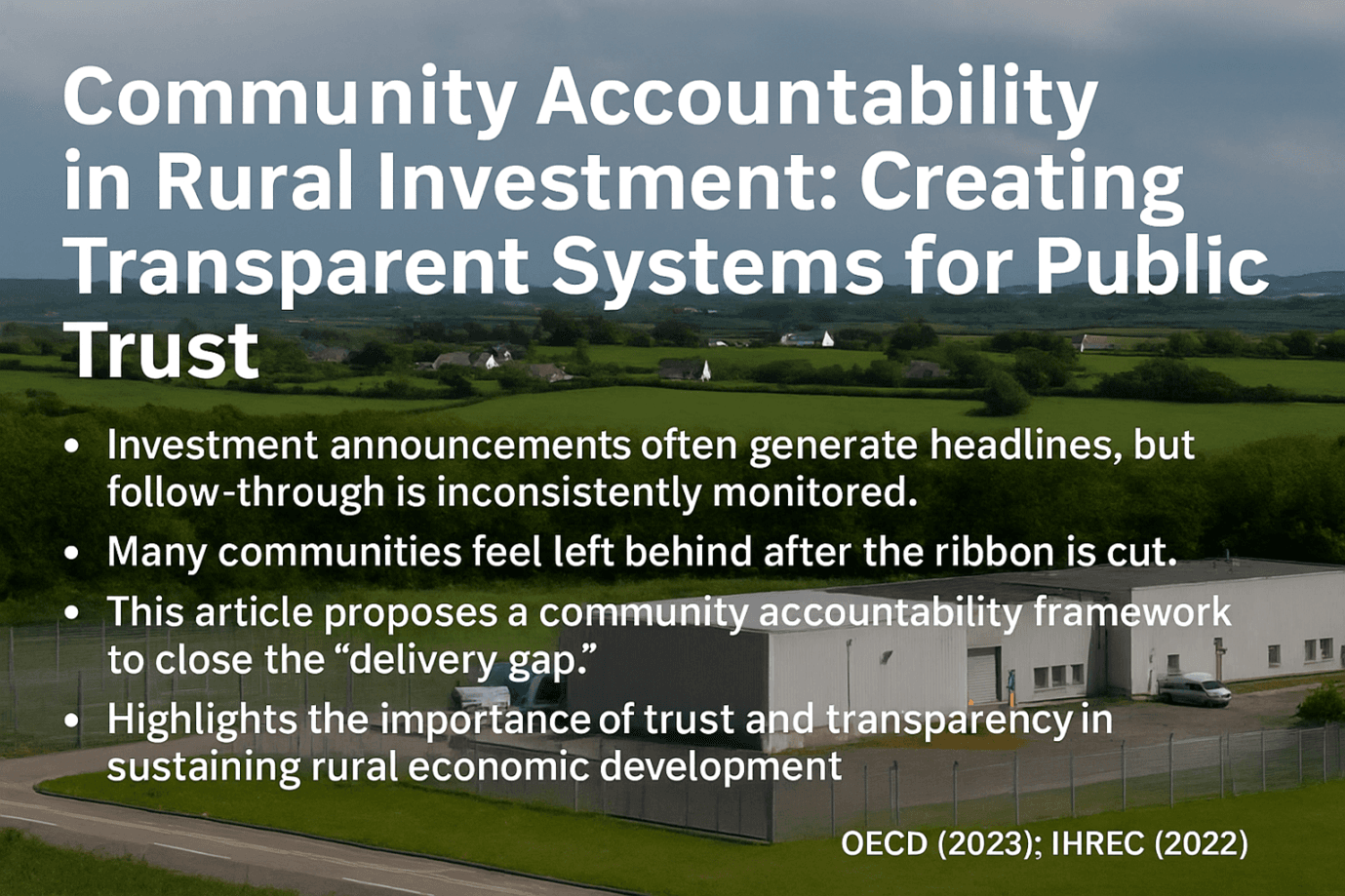

Community Accountability in Rural Investment: Creating Transparent Systems for Public Trust

Introduction: The Trust Gap After Investment

Across rural Ireland, foreign and domestic investment is increasingly seen as a solution to economic stagnation, job loss, and regional underdevelopment. Announcements of new business parks, data centres, or logistics hubs often generate political optimism, media coverage, and initial public enthusiasm. However, beyond the press releases and ribbon-cutting ceremonies, a more complicated reality often emerges—one in which the delivery of promised outcomes is poorly tracked, unevenly experienced, and insufficiently scrutinised.

This growing disconnect between investment intentions and lived impact has created what can be described as a “trust gap.” Communities who welcomed projects with hope frequently report feeling sidelined in the aftermath. Promised jobs do not materialise, infrastructure upgrades are delayed, and benefit-sharing mechanisms are poorly enforced or absent altogether. In the absence of formal structures for monitoring and public accountability, local confidence in both government and investors begins to erode.

This article argues that rural development will not be sustained through investment alone. It requires a complementary system of community accountability—one that empowers citizens, strengthens transparency, and ensures that investments deliver the social, economic, and environmental outcomes they claim to support.

Without such a framework, rural communities risk becoming passive hosts to externally driven agendas rather than active participants in shaping their own economic futures.

Drawing on best practices in rural governance and public duty frameworks (OECD, 2023; Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission [IHREC], 2022), the article proposes a set of tools and policy innovations designed to close the delivery gap. These include community-led oversight panels, open investment dashboards, and rural investment audits—all aimed at ensuring that investment not only arrives but actually works for the communities it claims to benefit.

What Gets Measured Gets Managed

In the aftermath of any major investment announcement, expectations are high. Communities anticipate jobs, improved infrastructure, increased demand for local services, and broader economic revitalisation. Yet, without clear systems of measurement, oversight, and transparent communication, these expectations are often diluted over time. Rural Ireland, in particular, has seen numerous instances where promised outcomes fade into ambiguity once the headlines subside. The absence of formal tools to track, verify, and report on investment delivery has created a chronic accountability vacuum, one that undermines both public trust and long-term planning.

This lack of structured follow-up is not unique to Ireland, but it is particularly damaging in rural regions where community cohesion and trust are often the foundation upon which economic cooperation is built. When investments arrive with limited local engagement or unfulfilled commitments, the damage is not just economic. It is relational. Residents may begin to perceive new projects as extractive rather than beneficial, especially if they bring visible costs such as traffic congestion, environmental degradation, or strain on housing and public services without corresponding improvements. Without mechanisms to measure the distribution of benefits and burdens, small towns can quickly lose faith in future development efforts.

Moreover, the mismatch between what is promised in planning or political statements and what is ultimately delivered has become a recurring source of frustration. For example, job creation figures are often cited during planning stages to justify fast-tracking or rezoning, yet there is no routine public system that verifies how many of those jobs were created, whether they were local, or if they were sustained beyond the first year. Similarly, commitments to use local suppliers or support training schemes may be made in principle, but fall by the wayside when procurement begins. The lack of measurable outcomes and community-accessible reporting contributes to the perception that communities are being spoken to, rather than engaged with as equal stakeholders.

International best practice points to the importance of monitoring and feedback systems that are co-designed with local stakeholders. The European Investment Bank, in its 2025 Municipalities Survey, emphasised the value of participatory reporting frameworks in regional infrastructure projects, especially when projects intersect with public services or land use planning. Such frameworks often include scorecards, public investment dashboards, and community tracking panels that assess key metrics such as employment outcomes, environmental compliance, and reinvestment commitments (European Investment Bank, 2025). These tools not only ensure accountability, but also build confidence in future collaboration.

Transparency International (2024) further highlights that corruption risks and inefficiencies in public-private partnerships are most prevalent where there is a lack of post-approval oversight. In rural areas, where political representation can be fragmented and resources stretched, these gaps are especially acute. It is not enough to celebrate the arrival of investment; it must be monitored rigorously, publicly, and inclusively. A well-functioning investment ecosystem treats the local population as active stewards, not passive hosts.

Closing the delivery gap begins with a simple principle: what gets measured gets managed. When rural communities have access to data, reporting tools, and participatory forums to hold investors and agencies to account, development becomes more credible and sustainable. It also allows successes to be celebrated properly. Too often, communities are suspicious not because they are resistant to change, but because they have learned that promises made at the top do not always translate into results on the ground. Building systems of measurement that are accessible, meaningful, and co-owned by communities is not just good governance—it is essential for economic resilience.

Empowering Local Oversight Structures

True accountability in rural investment cannot be achieved by government inspection alone. It must include the people who live, work, and raise families in the communities affected by development. For decades, rural communities have been consulted after decisions have already been made. They are often handed summary documents, invited to tokenistic town halls, or informed rather than engaged. To change this dynamic, rural investment governance must centre public participation not as an afterthought, but as a fundamental principle of how development is reviewed, shaped, and measured over time.

One of the most practical ways to institutionalise this participation is through the creation of Citizen Investment Review Panels. These panels, composed of a diverse cross-section of residents, business owners, farmers, educators, and civil society members, would be established in each county to oversee significant inward investment projects. Their purpose would not be to veto development, but to ensure that the commitments made during the planning and approval phases are clearly tracked and transparently reported. These panels would meet quarterly, have access to relevant data, and issue public assessments on delivery metrics such as employment creation, environmental compliance, and local economic impact.

In a country where rural development often happens in ways that are politically driven or developer-led, such panels provide a corrective mechanism—bringing power closer to those directly affected. They would act as a civic counterweight to private and political interests, ensuring that the long-term benefit to the community is not assumed, but demonstrated. Moreover, these panels would allow communities to participate in shaping the terms of Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) and hold investors to account when those terms are unmet. These are not radical ideas; they are grounded in international best practice.

The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (2022) has consistently argued for the implementation of the Public Sector Equality and Human Rights Duty across all forms of governance. This duty obliges public bodies to eliminate discrimination, promote equality of opportunity, and protect human rights in their decision-making processes. Applying this principle to rural investment, CIRPs would be a mechanism through which communities actively monitor whether the benefits of development are being distributed fairly and equitably, especially among traditionally underrepresented groups.

Furthermore, CIRPs offer a space for mediation and communication, rather than conflict. Too often, resistance to investment projects emerges because communities feel blindsided or ignored. By creating structured spaces where questions can be asked, feedback can be given, and data can be reviewed, tensions are reduced and partnerships can form.

The process also builds civic capacity. Training panel members in how to read planning documents, interpret environmental assessments, or understand procurement language fosters a stronger, more informed local leadership base.

It is also essential that these oversight structures are supported with real resources and legal recognition. Panels should have a small independent secretariat, access to technical expertise, and a statutory basis that ensures their voice must be heard in planning reviews and post-approval audits. Their findings should feed into local authority decision-making and be published annually as part of a county’s economic development report. As the OECD (2019) has noted in its rural policy frameworks, decentralised accountability mechanisms are most effective when integrated into a broader culture of participatory governance and responsive planning systems.

From a political standpoint, empowering local oversight structures does more than safeguard communities. It also builds confidence in the development process itself. Investors who engage with communities through structured, respectful processes are more likely to be welcomed, supported, and seen as partners rather than outsiders. For independent political representatives, panels also provide a platform to channel community concerns constructively, rather than reactively. They reduce the risks of opposition while increasing the legitimacy of both local government and incoming investment.

In short, empowering rural communities to oversee the outcomes of development is not a threat to economic progress. It is a foundation for it. Citizen Investment Review Panels create accountability through inclusion. They make the flow of public and private capital not just visible but relational, and in doing so, they bring democracy closer to the people most impacted by the decisions that shape their future.

Tools for Transparent Investment Governance

Transparency in rural investment is not simply about making information available. It is about designing tools and systems that allow communities to meaningfully understand, interrogate, and influence what is happening in their towns and regions. For too long, the details of major projects—ranging from promised jobs to environmental mitigations—have been confined to technical reports, planning conditions, or corporate updates that are either inaccessible or indecipherable to the public. This contributes to a growing sense that development is something done behind closed doors, rather than in open dialogue with the communities it impacts.

To address this, a new generation of transparent governance tools must be introduced at the county and national levels. These tools are not abstract ideals. They are practical, implementable instruments that allow rural residents, public officials, and investors to align around shared goals and verifiable progress. They also provide a platform for early issue detection and adaptive management, reducing the likelihood of conflict or non-compliance in the later stages of investment delivery.

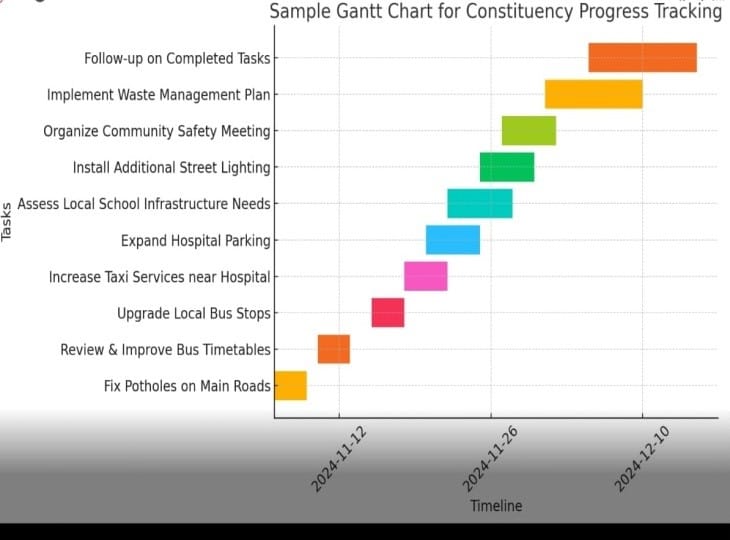

The first and most foundational tool is an Open Investment Dashboard. Hosted by local authorities and updated quarterly, this dashboard would publish live data on key project indicators, such as the number of jobs created, the proportion of those filled locally, training opportunities delivered, local supplier engagement, and environmental performance metrics. This tool would allow both citizens and councillors to monitor delivery in real time, ask informed questions, and compare outcomes against original commitments.

Dashboards must be user-friendly, searchable, and accessible across devices to ensure maximum usability.

Second, Community Benefit Scorecards can be introduced as a participatory evaluation method. These scorecards, completed annually by Citizen Investment Review Panels and made public, would assess the qualitative dimensions of an investment’s impact. Categories could include trustworthiness of the investor, responsiveness to community concerns, contribution to public infrastructure, and visibility of reinvestment. The process of scoring itself is as important as the outcome, because it builds a shared vocabulary around what good investment looks like and gives communities a structured space to reflect, give feedback, and set future expectations.

Another essential tool is the implementation of Public Access Impact Statements. These concise, non-technical summaries would accompany every significant investment proposal, outlining the economic, environmental, and social impacts in plain language. Prepared jointly by planning authorities and independent reviewers, they would ensure that residents understand what is being proposed and what conditions have been attached to approval. These statements should also be updated post-approval to reflect what has actually been delivered, reinforcing a culture of longitudinal transparency.

Finally, rural counties should experiment with Participatory Monitoring Frameworks tied directly to planning conditions. Rather than relying solely on statutory enforcement by planning departments, these frameworks would build in community roles for observing, recording, and reporting on compliance. Residents could track construction progress, monitor environmental commitments, or document disruptions through community liaison forums. These forums would submit quarterly reports to both the council and the investor, helping to de-escalate concerns before they become crises and creating a feedback loop that keeps all actors accountable.

Each of these tools is designed not just to observe investment, but to democratise it. By making performance visible and participatory, these mechanisms create a different kind of development culture—one where accountability is not a threat, but a shared value. As the European Investment Bank (2025) notes in its recent review of infrastructure governance, the most successful public–private investments are those that embed transparency and citizen participation from the outset. Similarly, the European Commission (2022) has argued that inclusive procurement and benefit monitoring practices are essential for ensuring that development aligns with community well-being, not just economic output.

Rural communities are ready for these tools. They have the local knowledge, the motivation, and increasingly, the organisational capacity to use them effectively. What they need is political support, policy integration, and technical resources. Building a transparent rural investment governance system is not about creating bureaucracy. It is about creating legitimacy. And in a time when public trust is hard-won and easily lost, legitimacy may be the most valuable return on investment of all.

Policy Recommendations: Making Accountability Routine

To truly embed public trust in rural investment, transparency must become standard practice, not a voluntary act of goodwill. While community dashboards, citizen review panels, and benefit scorecards are important tools, their success depends on being backed by policy. Rural Ireland requires not only new governance models, but new governance rules—structures that define responsibility, enable oversight, and protect the public interest long after the initial investment is made. The following policy proposals are designed to transition community accountability from aspiration to institutional reality.

The first recommendation is the mandatory use of Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) for all inward investment projects above €10 million or any development that exceeds specified thresholds for environmental or infrastructural impact. These agreements should be legally binding, negotiated early in the planning process, and co-developed with residents through Citizen Investment Review Panels. They should detail concrete commitments regarding job creation, skills development, infrastructure contributions, environmental protection, and reinvestment into community initiatives. Critically, these agreements must include enforcement clauses and review timelines to prevent them from becoming symbolic gestures.

Second, a Rural Investment Audit Requirement should be included in the final phase of all major projects. Just as environmental impact assessments are a routine part of planning approval, so too should rural economic and social audits be standard at project closure or milestone intervals. These audits would assess whether the project met its original goals, how benefits were distributed, and what follow-up is required. They should be publicly available, conducted by independent experts, and reviewed by local councils with input from Citizen Investment Review Panels. As the OECD (2019) emphasises, post-project evaluations are essential for adaptive policy-making and long-term learning.

Third, national agencies such as IDA Ireland and Enterprise Ireland should be required to include public performance reporting mechanisms for all companies receiving financial incentives, grants, or fast-tracked access to land and services. This would include reporting not only on economic outcomes such as export growth or tax contributions, but also on social metrics such as job quality, community engagement, and environmental sustainability. These reports should be standardised and stored in a national open database that links to local authority dashboards, enabling cross-sector analysis and public comparison.

Fourth, Damien proposes the establishment of a Rural Development Ombudsman Office with statutory authority to receive complaints, investigate claims of non-compliance, and issue binding recommendations or enforcement referrals. This office would serve as an independent mechanism to protect rural communities against project underperformance, planning abuses, or broken investor commitments. It would provide an accessible and affordable alternative to litigation, giving communities a trusted recourse when other channels fail. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (2022) has noted that the right to redress is a foundational element of good governance and public trust.

Finally, a national Rural Investment Governance Framework should be developed, in consultation with rural stakeholders, to standardise how investment is planned, approved, tracked, and reviewed. This framework would align local practices with national priorities, define shared metrics, and establish guidelines for community engagement, transparency tools, and post-investment oversight. It would ensure consistency across counties, while still allowing for place-based adaptation. By formalising what is currently informal and fragmented, this framework would give both communities and investors clarity, confidence, and credibility.

These policy shifts are not about adding new layers of red tape. They are about modernising our governance architecture to reflect the complexity of today’s rural development challenges. As IDA Ireland (2025) and the European Commission (2022) both acknowledge, sustainable regional investment depends not only on attraction strategies, but on delivery systems that are resilient, accountable, and inclusive.

Ireland has the tools, the legislative foundation, and the public appetite to lead on this agenda. What is needed now is political will. And that begins with listening to rural communities—not only at the beginning of a project, but all the way through to its conclusion.

Conclusion: From Passive Host to Active Partner

For rural Ireland to thrive in the long term, it must move beyond the model of passively receiving investment toward a future where communities are recognised as full partners in shaping, evaluating, and sustaining economic development. This means embracing transparency not as a bureaucratic exercise, but as a relational one—rooted in trust, accountability, and mutual respect between investors, government, and local people. Communities that are informed, engaged, and empowered are far more likely to support development and ensure its success.

The reality on the ground is that many rural areas have become skilled at adapting to policy changes, economic shocks, and infrastructure gaps. But they have not been given equal access to the tools of governance that ensure promises are kept and outcomes are fairly distributed. Investment without oversight creates a fragile social contract, especially when expectations are high and delivery is uneven. Rebuilding public trust begins with recognising that every job promised, every benefit claimed, and every decision made must be tracked, reviewed, and made visible.

This article has proposed a practical roadmap for embedding community accountability in rural investment. It has outlined structures such as Citizen Investment Review Panels, investment dashboards, rural impact audits, and enforceable benefit agreements. These mechanisms are not radical. They are overdue. When placed in the hands of capable local leaders and informed residents, they form the foundation for a stronger, more resilient development process—one that welcomes investment but does not surrender to it.

The shift from passive host to active partner is as much cultural as it is administrative. It requires political leadership that respects the lived knowledge of rural people and systems that convert that knowledge into action. As Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, and Tomaney (2017) remind us, the success of regional development lies in recognising the agency of place and the capabilities within it. Rural Ireland has both. What it now needs is the space to lead.

The next generation of investment will be judged not only by how much capital it brings in, but by how deeply it builds public trust. That trust can no longer be assumed. It must be earned, measured, and protected. And it starts with accountability.

References

European Commission. (2022). Sustainable and inclusive procurement tools for regional development. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/index_en.htm

European Investment Bank. (2025). Municipalities survey 2024–2025. https://www.eib.org/en/publications/20250028-eib-municipalities-survey-2024-2025

Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission. (2022). Strategy statement 2022–2024. https://www.ihrec.ie/app/uploads/2022/02/IHREC_StrategyStatement_FA-v2.pdf

IDA Ireland. (2025). Adapt intelligently: A strategy for sustainable growth and innovation, 2025–2029. https://www.idaireland.com/latest-news/press-release/ida-ireland-launches-new-five-year-strategy

OECD. (2019). OECD principles on rural policy. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/rural-service-delivery/oecd-principles-on-rural-policy.html

OECD. (2023). Community wealth building for a well-being economy. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/providing-local-actors-with-case-studies-evidence-and-solutions-places_eb108047-en/community-wealth-building-for-a-well-being-economy_afdeefcd-en.html

Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2017). Local and regional development (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315767673

Standring, A., & Fisher, M. (2022). Working-class political representation: Between populism and policy neglect. Critical Policy Studies, 16(2), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1930776

Transparency International. (2024). Local governance and anti-corruption in investment. Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/en/publications